INTRODUCTION

I produced the bones of this dit to help the son of a fellow MCDOA member with his university project. It may interest others who wish to learn one particular officer's background and motives for joining the Minewarfare & Clearance Diving Branch.

PREVIOUS SERVICE BACKGROUND

I joined the RN at Britannia Royal Naval College (BRNC) Dartmouth on 2 May 1971 as an 18-year old Supplementary List (SL) Seaman (otherwise known as Executive branch (X)) Specialist cadet. My original commission was for 16 years with an 8 year break-point but I was later awarded a Full Career Commission to the age of 50. My American High School diploma and grades were recognised as the equivalent of 5 GCE ‘O’ levels.

Before leaving Dartmouth, I was interviewed by my Divisional Officer as to my sub-specialist aspirations. My options as an SL Seaman Officer were:

Little tas (Torpedo & Anti-Submarine)

Little g (Gunnery)

Little n (Navigation) or DNDO (Destroyer Navigation & Direction Officer)

H (Hydrography)

ATC (Air Traffic Controller)

Long MCD (Minewarfare & Clearance Diving)

In my view, the only two ‘full’ qualifications available were H and MCD. An immediate decision was not required because I still had to get through my year at sea in the Fleet as a Midshipman, pass my Midshipman’s Board and then undertake my first proper job as an Acting Sub Lieutenant to obtain my bridge watch-keeping certificate. I regarded the prospect of Hydrography as boring and remember expressing some interest in MCD (when I found out what it meant) before promptly forgetting about it for a couple of years as I immersed myself in my studies at sea.

MOTIVATION

Having read a lot of naval writers including Winton, Forester, Reeman and Monsarrat and listened to ‘The Navy Lark’ on the radio as a boy, all I wanted to do when I joined the Navy was to visit exotic places, impress girls and stand on the bridge saying, “Right hand down a bit...” I had toyed with the idea of joining the Fleet Air Arm and even sent off a coupon from the Daily Express for a recruiting brochure when I was 10. I still have the brochure and the 1962 rates of pay are particularly interesting e.g. Basic Pay for a married Lt Cdr was £1,241 per year plus Flying Pay £401 and Marriage Allowance £401. In the event, the nearest I got to flying was a trip in a Chipmunk at RNAS Yeovilton during my Junior Officer's Air Acquaint Course as a midshipman.

My first proper job in the Navy was as Navigating Officer of HMS Laleston. Having completed my Midshipman’s year in HMS Torquay and passed my Midshipman’s Board, I joined HMS Laleston as an Acting Sub Lieutenant in April 1973 before I had even earned my bridge watch-keeping certificate let alone undertaken any special course for the job. We SLs were sent straight into the lion’s den.

HMS Laleston (a converted coastal minesweeper) was the diving

tender attached to HMS Vernon, home of the RN anti-submarine, minewarfare

and diving school in Portsmouth. It is now

the millennium waterside development called Gunwharf Quays. Laleston

spent her winter months based at Tarbert Loch Fyne or Oban to support

deep diving training around the west coast of Scotland.

In the summer when the weather was kinder, she was based at Falmouth to

support deep diving training around the West Country.

She was a very private ship and we spent our ‘free’ weekends visiting

small but friendly ports up and down the coast where we were guaranteed a good

run ashore and a welcome from the locals.

During my 2½ years in Laleston I encountered many naval divers and became fascinated by them and their work. My Commanding Officer was an MCD officer and even the First Lieutenant left us to undertake his own MCD course.

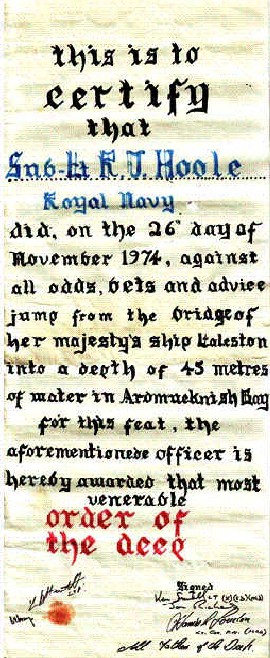

One day, I foolishly allowed someone to hear me expressing my interest in diving. The assembled MCD officers decided I should undertake an unofficial ‘aptitude test’. As the ‘certificate’ on the left states, we were anchored in 45 metres of water in Ardmucknish Bay on the west coast of Scotland.

First I had to dress in a rubber dry suit. Having managed to climb in through the top of this ‘dry bag’ and have a neck seal attached, I was then asked to jump off the ship’s stern (about 2 metres high) into the water. Next, I was invited to jump off the acoustic deck (about 4 metres high). Finally, I had to jump off the bridge wing (about 7 metres high). With the entire ship’s company watching from below, I managed this too. Unfortunately, when I hit the surface the metal clamp securing the thin rubber neck seal to the rest of my dry suit came adrift and my suit rapidly started to fill with water. Luckily the Gemini dinghy used as a safety boat zoomed in and its crew recovered me before I topped up completely and sank to the sea bed.

As a wheeze, the ship's Chief Bosun's Mate had rigged a plank at the masthead but I was excused from jumping off it. In the circumstances, this came as quite a relief.

My aptitude was rounded off with a short dive from the stern in a clunky but comfortable old SABA (Swimmer's Air Breathing Apparatus). As I hung suspended in the crystal clear water and looked at the sea bed and the hull of the ship, I found I could breathe easily and move freely in 3 dimensions. I thus became hooked on diving for the rest of my service career although many of my subsequent dives were nowhere near as pleasant.

ROAD TO QUALIFICATION

Late in 1974, I was called by my appointer and asked if I wanted to join the Leander Class frigate HMS Minerva. She was due to sail for a lengthy deployment as the West Indies Guard Ship. It was the stuff from which dreams are made. The only hitch was that she needed a Ship’s Diving Officer (ShDO) so I would have to complete the 4 week course before I joined. Thus, January 1975 found me conducting endless jackstay endurance swims on SABA in a freezing Horsea Lake just to the north of Portsmouth. As my course officer was one of the MCD officers who had signed my unofficial diving aptitude ‘certificate’ on board Laleston, I was put straight on course after passing a diving medical examination at HMS Vernon.

I spent 8 highly enjoyable months in Minerva as her Diving Officer sailing from one Caribbean island to the next with several opportunities for diving, most of which I found myself supervising. For the second half of our deployment I had a Deputy Diving Officer (a midshipman who later became an MCD Commander) and his presence enabled me to get in the water more often myself.

Towards the end of our deployment, I volunteered for the Long MCD Officer’s (LMCDO) course. My Commanding Officer attempted to dissuade me because he regarded the specialisation as career-limiting with few opportunities for promotion but I insisted this was what I wanted to do. He ended up recommending me for the course.

Pre-requirements for LMCDO students included the achievement of at least a year as a ShDO and 1,000 minutes underwater. I had only achieved 7 months as a ShDO and 400 minutes underwater but the requirement was waived in my case. No aptitude test was administered in those days so drop-out rates were normally fairly high in the early stages of the course. All the members of my own unusually large course were highly motivated and we only ended up having one member back-classed.

THE LONG MCD OFFICERS' COURSE

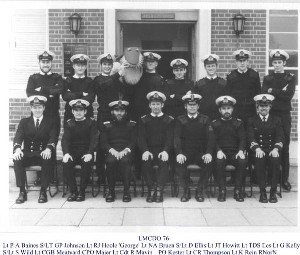

I qualified as a MCD Officer on the 1976 Long MCDO Course. Initially we had 11 RN students plus a Norwegian naval officer. A Canadian Diving Officer joined us for the Minewarfare module. The characters on the course and their experiences and activities during the year deserve their own story. One day I might get round to writing it; well, at least the publishable bits.

1976 LMCDO Course plus 'George' - a motley crew

The one-year course was split into three terms and comprised:

The Diving module with theory taught at HMS Vernon and shallow water practical closed-circuit re-breather oxygen and mixture diving in Horsea Lake and in the dockyard followed by open water searches at Portland and deep self-contained closed-circuit and surface demand mixture diving at Falmouth.

The Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) module at the Defence Explosive Ordnance Disposal School, Chattenden including demolitions at the Lydd range.

The Minewarfare module with theory at HMS Vernon and sea training in the Forth.

CHANGES WITNESSED IN ROYAL NAVY DIVING

Since those halcyon days, the main change I have witnessed in RN Diving has been in the area of safety. For many years, the RN was not subject to commercial diving safety standards; not that these were particularly stringent in the early days of North Sea diving. The MOD was even granted a blanket waiver when Health & Safety (H&S) legislation was introduced. The incumbent RN Superintendent of Diving (SofD) saw this legislation as unwanted interference in the conduct of naval diving training and operations. We went on using the same old procedures and diving kit which was subsequently found to be dangerous although we had surprisingly few incidents or accidents over the many years it was in service. I think this owed much to our traditional seamanship which included good planning, high standards of training and experience and, above all, common sense.

A more enlightened RN SofD recognised that the application of stringent H&S standards could actually provide the justification for better diving equipment. This was a time when the phrase “Health & Safety” could open up new pots of MoD money for improvements all round. The upshot was that, even while we were not bound by H&S legislation, we could still use it to our advantage for the procurement of more modern equipment. New unmanned diving test technology showed that much of our old diving equipment failed to meet breathing resistance criteria and built-in redundancy for safety. This resulted in replacing or modifying most of it including our dependable old WW II vintage Clearance Diving Breathing Apparatus (CDBA).

In 1996, Michael Portillo as Defence Secretary dictated that the MOD would henceforth be subject to HSE legislation for the procurement of all new equipment and that equipment already in use would be brought up to standard where at all possible. H&SE regulations were also to be followed for all normal training and exercises; a waiver was only allowed for live operations. This is why we now wear Adjustable Buoyancy Aids (inflatable jackets) with all our current diving sets instead of relying on suit inflation for dry suits or no buoyancy aid at all with wetsuits. We also have underwater voice communications instead of relying on manually pulling the lifeline to pass signals from supervisor to diver and vice-versa. All our ship-borne recompression chambers now have two compartments to allow a medical specialist to enter. They are also larger to accommodate an attendant as well as a diver – no more one-man chambers. As for our CDBA, it is now the size and weight of a refrigerator owing to its back-up breathing systems and our twin-bottle air sets now have contents gauges instead of the old practice of breathing from one cylinder then equalising from the other when the first was empty. A diver was meant to surface after his second equalisation.

TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCEMENTS

For an understanding of technological advances over the years, it is probably helpful to divide Clearance Diving into its various roles. These include:

Underwater EOD

Underwater Engineering

Maritime Counter-Terrorism

Clearance Divers are now equipped with far better equipment for the detection, identification and disposal of unexploded ordnance (UXO). This ranges from protective clothing for a wide range of roles and conditions worldwide to portable communications systems that allow digital images of unknown ordnance to be transmitted back to base for advice on its disposal or rendering safe. Purpose-built vehicles and support boats are provided although there is a painful lack of Fleet Diving Tenders for deeper water training and operations. Better environmental support means that the conditions in a particular area can be accessed and their effect on diving operations can be predicted more easily.

Tremendous advances have been made in divers’ life-support equipment over the past 30 years. A self-contained clearance diver can now descend to 80 metres whereas he would have required surface demand breathing apparatus to do this before i.e. his gas would have been supplied through a hose from the surface. Microprocessors and sensors built in to his breathing apparatus ensure he receives the correct mixture of gases for the depth involved. Larger more effective fixed and portable surface recompression chambers are now available for support platforms and vehicles.

Modern materials mean divers are now better insulated from the cold while performing their tasks and through-water communications allow them to speak clearly with each other and with the surface support team. Acoustic beacon tracking systems permit divers to navigate with precision on the seabed instead of having to lay heavy gridlines and sinkers. Divers can even use GPS satellite navigation via an aerial floating on the surface. Divers are also better equipped with hand-held sonar to detect seabed obstacles and explosive devices – many of these have ‘head-up’ displays fitted in his mask. Swimmer ‘tugs’ are available that can propel a diver at faster speeds to search greater areas with less fatigue.

The downside of all this technology is that a diver now has much more equipment to carry and suffers the risk of ‘information overload’ as he tries to maintain his depth and swim safely while monitoring his hi-tec navigation aids and sensors and recording the results of his task.

Underwater Engineering

New hydraulic tool packs permit a far greater range of underwater engineering tasks to be performed. Image intensifying underwater video cameras often provide a better image of the task than the diver’s own eyes. Ironically, an inflatable watertight housing called ‘Habitat’ even allows divers to work underwater on the hulls of ships and submarines while staying dry.

Non-destructive testing equipment enables divers to check the integrity of structures, pipes and materials without damaging them.

Paradoxically, one of the greatest benefits has been the development of Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs). These have complemented divers, particularly in deep recovery or salvage operations, by providing a ‘swimming eyeball’ through which the diver’s progress can be monitored by the surface support team.

Perhaps the greatest advance in this area is the procurement of the new improved Swimmer Delivery Vehicle (SDV - an open submersible) that can carry a team of divers covertly to their target area. The SDV can be delivered great ranges in a dry deck hangar mounted on a submarine. The hangar can then be flooded to allow the SDV and its cargo of divers to travel the final few miles.

FUTURE OF THE MCD SPECIALIST

I consider it important to retain a corps of RN minewarfare specialists because the mine is likely to be the weapon of choice for everyone from large nations to terrorist groups; it is cheap, plentiful, highly effective and more advanced versions are being developed all the time. Even the implied threat of mining can cause concern, especially in critical waterways and the entrance to ports and installations.

The most effective officer to command a Clearance Diving team is a Clearance Diving Officer and the most effective officer to command a Mine Countermeasures Vessel (MCMV) or even a squadron of MCMVs is a Minewarfare (ideally an MCD) officer.

It is important to regard Clearance Diving as an integral part of Mine Countermeasures (MCM). While new types of ROVs such as the one-shot disposal system and Autonomous Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (AUUVs) are likely to replace divers for many roles, a Clearance Diving capability remains a useful weapons system to have ‘in the bag’. In waters of low or nil visibility, a diver’s fingertips are still essential to perform certain delicate tasks. Apart from underwater engineering, these might include the identification and rendering safe of newly discovered types of ordnance (especially mines) so they can be recovered and exploited to find out their secrets and help develop countermeasures.

The Minewarfare part of the MCD role has come more to the fore, especially for officers, and there are now officers who specialise solely in MW. Younger MCDOs are needed to run the weapons systems of MCMVs, indeed the MCDO is an important member of the diving team. As MCDOs age, their focus becomes more concentrated on Minewarfare than Diving. Operationally, they are needed to fill the staff jobs as advisors to Task Group Commanders and shore-based Commanders. They are also needed to take their place in the Defence Procurement Agency and Naval Support to ensure the right sort of equipment is brought into service.

I can see the diving side of the house concentrating more on underwater engineering in future because it is so cost-effective in comparison to docking ships and submarines. More of the MCM diving tasks are likely to be performed by ROVs and there may well be a role for divers as ‘underwater operators’ able to employ ROVs as well as perform tasks themselves when they are beyond an ROV’s capability.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Minewarfare is still a core task (or at least a particularly important enabling task) of the RN and I believe the MOD still sees a role for the MCD specialist. Recent conflicts (Suez Canal, Falklands, Red Sea, Gulf I & 2) have shown that the mine threat remains significant. However, with the possible exception of a few officers who might specialise solely in Minewarfare (there are probably not enough billets to employ the purely CD specialist officer), MCDOs must also be trained in general warfare operations as Principal Warfare Officers. This is not only a requirement to meet the complex warfare situations of today where MCMVs work within larger Task Group organisations (they are no longer sent off to play on their own), but is also broadening for the officer so he can have a fulfilling career beyond junior rank. You need more than one string to your bow if you are to compete with less narrowly specialised officers and fulfil the requirements of higher ranking posts having greater and broader responsibilities.

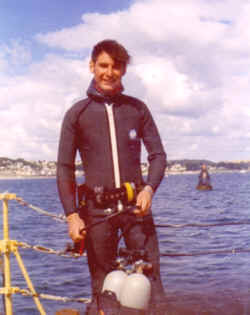

Hoole at Falmouth during LMCDO Course